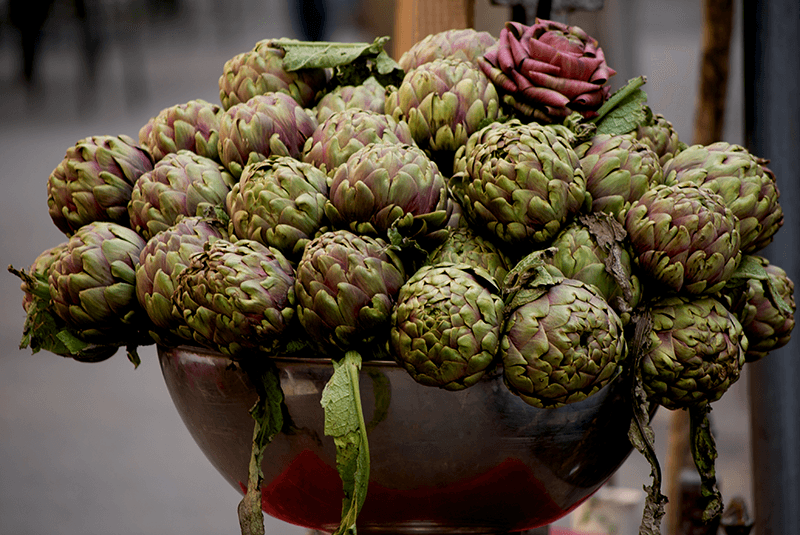

The Italian artichoke, il carciofo

COMPOSITAE: The Composite Family

Herbs or shrubs with alternate or opposite leaves.

Flowers or florets collected several together into a Head surrounded by an involucre of bracts, the whole Having the appearance of a single flower. From Handbook of the British Flora, by Bentham and Hooker, page 230

Daisies, those ubiquitous members of the compositae family which we all know and love, have many edible relatives. Two of these are currently in Italian markets and greengrocers so if you are visiting Italy it is worth giving them some attention when preparing meals or going to a restaurant.

The months from October to May are when both the well-known Globe artichoke (Italian carciofo,) and the less well-known Jerusalem artichoke (the Italian topinambur,) find their way to our tables to delight our palates.

The Jerusalem artichoke, helianthus tuberosus, has an interesting history and an even more interesting name. It is native to north eastern USA and Canada and was a staple food of the native Americans for thousands of years. When the French explorer Samuel de Champlain sent the first samples to France in the early 17th century he noted that it tasted of artichoke (globe).

This stuck even if the resemblance in flavour is not immediately obvious. The Jerusalem part is more difficult to pin down. Perhaps it is a corruption of the Italian word for sunflower to which it is closely related, girasole. But why the French or English should use or know the word girasole is anybody’s guess. Another possibility is that the early settlers in north America named it thus thinking that they were in “the new Gerusalem”.

The French and Italians, at least, call it topinambur by naming it after a tribe of American (or South American) Indians who were thought to cultivate and use it, (the Topinambu or Topinamboults). So the plant is clearly misnamed by us which doesn’t stop it from being a very interesting vegetable!

The Jerusalem artichoke plant grows from a tuber, the edible part, and grows very vigorously up to some 4m in height. In late summer it flowers prolifically with bright yellow flowers rather smaller than sunflowers. The tubers, which are at their best in the winter months, are very nutritious and very similar to potatoes except that instead of starch they contain the carbohydrate inulin (NOT insulin) made up of fructose units and therefore tolerated by diabetics. They should be cooked in any way that potatoes may be cooked and there are hundreds of recipes available. Personally I find them delicious when simply steamed and served with butter.

The Globe artichoke, cynara scolymus, is a native of the Mediterranean regions but certainly grows well in Britain (one had a fine crop of them in Northern Ireland, for example). It has a much more easily understandable name. The part we eat is the unopened flower bud which is globe shaped. The artichoke part comes from the Italian articiocco, which in turn comes from an Arabic word. It seems to refer to the spiny heart of the bud which tends to choke one if it is not removed beforehand.

Basically the plant is a thistle which can be as much as 2m high when flowering. It is often to be seen at the back of herbaceous borders in gardens where it adds height and colour. The unopened buds, which mature during the winter months, have been eaten by the peoples of the region from time immemorial (Etruscans, Greeks, Romans, Arabs) and it remains a very important food crop to this day. Again, many recipes are available but perhaps the simplest is the one for carciofo alla romana. In essence (and the recipe is easily found in any cook book or on internet) this is an artichoke stuffed (after removing the ‘choke’) with breadcrumbs and garlic, mint and parsley and then boiled to tenderness. Absolutely delicious!

First cousin to the globe artichoke is the Cardoon, cynara cardunculus, another thistle. Here, the edible parts of the, in Italian, cardo, are the leaves and leaf-stalks. These, available in most vegetable markets, are boiled and served with a cheese sauce, fried or even eaten raw with a suitable dip.

With us all year round is the other great daisy delight, chicory, cichorium intybus and cichorium endivia. The wild plant, which is very common, produces those startlingly electric blue flowers by the roadsides all over Europe (except the far north) during the summer months but has been cultivated as a food plant for thousands of years. Its multifarious varieties are with us as cicoria, a green vegetable for boiling (rather bitter), puntarelle (leaf stalks split and seasoned with anchovies), indivia, radicchio, scarola and endive, used as green salad leaves or stuffed and roasted in the oven . The roots of the plant are roasted and serve as a substitute for coffee since the dried, roasted and ground roots give a rather bitter brew.

Dandelion, taraxacum officinale, another ‘daisy’, is also eaten as a green salad vegetable (in France various varieties are actually cultivated) and its roots, suitably roasted, are also used as a coffee substitute. We are used to considering dandelions as the archetypal ‘weeds’.

Italy abounds in these vegetables; other European countries perhaps less so. Do try them while you have the chance.