Anna Magnani was born in Rome, she was brought up in poverty by her maternal grandmother in a slum district of the city. After some education at a convent school, she enrolled at Rome’s Academy of Dramatic Art and sang in nightclubs and cabarets to support herself. Due to her work in nightclubs, Magnani was dubbed the Italian Édith Piaf.

In 1927 she acted in the screen version of La Nemica e Scampolo. She had also been in the stage production. She met Italian filmmaker Goffredo Alessandrini in 1933 and the two were married in 1935. He was one of the first Italian filmmakers to adapt the new sound technology used in American cinema. Her marriage to Alessandrini ended in 1950, and she never married again. Magnani once said, “Women like me can only submit to men capable of dominating them, and I have never found anyone capable of dominating me”.

In 1941, Magnani starred in Teresa Venerdì, (“Friday Theresa”) which the writer and director, Vittorio De Sica, called Magnani’s “first true film”. In it she plays Loletta Prima, the girlfriend of Di Sica’s character, Pietro Vignali. De Sica had called her laugh, “loud, overwhelming, and tragic”.

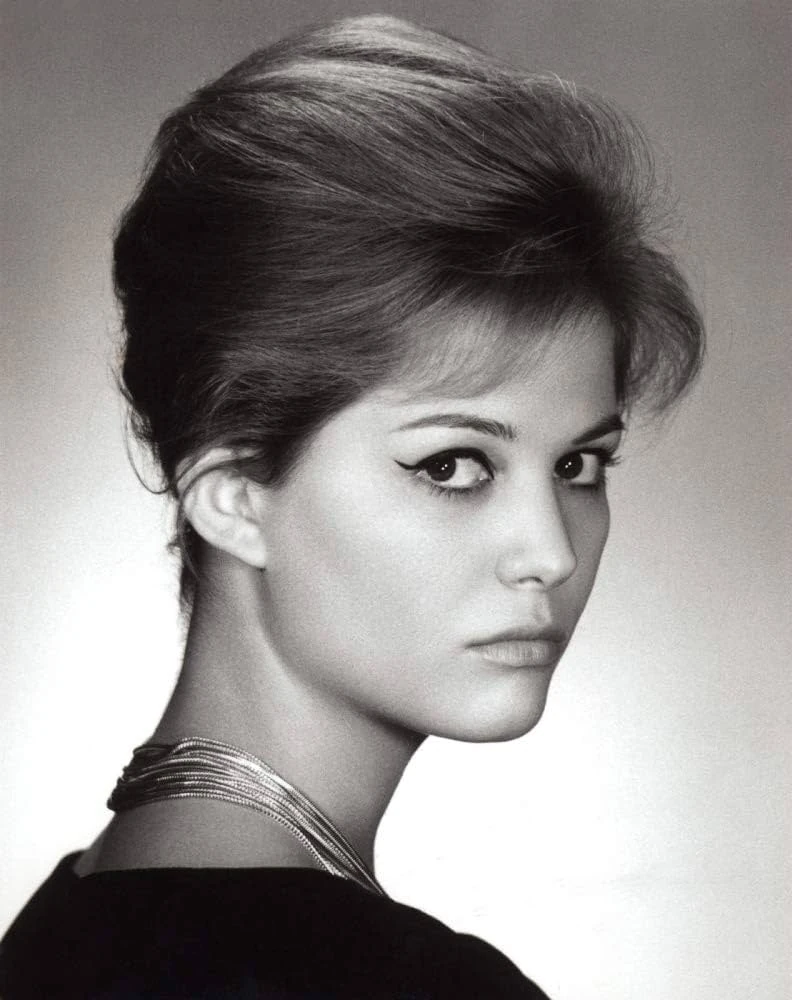

She had worked in films for almost 20 years before gaining international renown as ‘Pina’ in Roberto Rossellini’s neorealist milestone Roma, Cittá Aperta. (also known as Rome, Open City, 1945). Her harrowing death scene remains one of cinema’s most devastating moments. In Italy (and gradually elsewhere) she soon became established as a star, although she lacked the conventional beauty and glamour usually associated with the term. Slightly plump and rather short in stature with a face framed by unkempt raven hair and eyes encircled by deep, dark shadows, she attracted through her seething earthiness and volcanic temperament.

Magnani was Rossellini’s second choice to play the role of Pina. He had originally wanted Clara Calamai, the lead of Ossessione, (a part Luchino Visconti had originally offered Magnani) but she was already under contract and working on another film. Rossellini almost had to resort to his third actress choice because Magnani demanded she be paid the same amount of money the male lead, Aldo Fabrizi was getting. The difference in salary was only 100,000 lire, and was really over principle more so than price. Rossellini, whom she called, “this forceful, secure courageous man”, was her lover at the time, and she was to go on and collaborate with him on other films.

Other collaborations with Rossellini include L’Amore, a two part film from 1948: The Miracle and The Human Voice (Il miracolo, and Una voce umana.) In the former, Magnani, playing a peasant outcast who believes the baby she’s carrying is Christ, plumbs both the sorrow and the righteousness of being alone in the world. The latter film, based on Jean Cocteau’s play about a woman desperately trying to salvage a relationship over the telephone, is remarkable for the ways in which Magnani’s powerful moments of silence segue into cries of despair. One could surmise that the role of this unseen lover was Rossellini, and was based on conversations that took place throughout their own real-life affair.

In 1951’s Luchino Visconti’s Bellissima she plays Maddalena, a blustery, obstinate stage mother who drags her daughter to Cinecittà for the “Prettiest Girl in Rome” contest. When she realizes that the studio heads are laughing at her daughter’s screen test, a shattering close-up of Magnani’s face reveals rage, humiliation, and maternal love. She starred as Camille, a woman torn between three men, in Jean Renoir’s 1953 film Le Carrosse d’or (also known as The Golden Coach). Renoir called her “the greatest actress I have ever worked with.”

As the widowed mother of a teenage daughter in Daniel Mann’s 1955 film of Tennessee Williams’s The Rose Tattoo, Magnani’s adroit, mercurial performing offsets the hammy Method acting style of co-star Burt Lancaster. It wasn’t until then that she broke into Hollywood mainstream cinema with her first English speaking role. Playing Serafina Delle Rose in The Rose Tattoo, she won the Best Actress in a Leading Role Oscar. Tennessee Williams wrote it and based the character of Serafina on Magnani, since the two were good friends. It was originally put on stage starring Maureen Stapleton, because Magnani’s English was too limited at the time for her to star. Magnani worked with Williams again in his 1959 film, The Fugitive Kind, where she played Lady Torrance and starred opposite Marlon Brando.

The Wild, Wild Women (1958) is notable for pairing Magnani, as an unrepentant streetwalker, with Giulietta Masina in a women-in-prison film. In Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Mamma Roma (1962), Magnani is both the mother and the whore, playing an irrepressible prostitute determined to give her teenage son a respectable middle-class life. Mamma Roma, is one of Magnani’s critically acclaimed films, yet it wasn’t released in the United States until 1995, for having been deemed too controversial.

It was after this role along with her many other parts of playing poor women that Magnani was quoted in 1963 as having said, “I’m bored stiff with these everlasting parts as hysterical, loud, working class women.”

Magnani made her final film performance as Rosa in The Secret of Santa Vittoria. Towards the end of her career, Magnani was quoted as having said, “The day has gone when I deluded myself that making movies was art. Movies today are made up of…intellectuals who always make out that they’re teaching something.”

She died at the age of 65 in Rome, after a long battle with pancreatic cancer. A huge crowd gathered for her funeral in a final salute that Romans usually reserve for Popes. She was provisionally laid to rest in the Roberto Rossellini’s family mausoleum, her favorite director and longtime friend. She now rests in the Cimitero Comunale, San Felice Circeo, Lazio, Italy.

Italian Dating & Chat for Italian Singles

Virtually meet thousands of like-minded Italian singles and connect at lightning speed; on desktop, tablet, and your beloved phone. Chat into the wee hours of the night if you’d like. Post photos, share your interests and dreams-we’ll help you look your best while you do it.Here we make it easy to meet Italian singles and feel things out first so when you do go on that first date, or meet for espresso, you can relax and be yourself. Try it now!