The Italian avant-garde cinema scene between 1911 and 1919 was a brief but transformative era, driven largely by the influential and radical movement known as Futurism. Born as an artistic and social revolt against tradition, Futurism celebrated modernity, movement, and the energy of the machine age. This was particularly true in Italian cinema, which, though in its infancy, became a compelling platform for Futurist ideas. The Manifesto of Futuristic Cinematography, dated 1916, is a landmark document that captured the revolutionary vision of Italian artists of the time. Among its notable signatories were Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Armando Ginna, Bruno Corra, and Giacomo Balla—leading figures in Futurism who believed in cinema’s potential to express the modern human experience in entirely new ways.

The Birth of Futurist Cinema: Challenging Tradition and Embracing the New

Futurism, as conceived by Marinetti in his 1909 manifesto, glorified speed, technology, youth, and violence, viewing these as the key attributes of a new age that rejected traditional aesthetics. Cinema, being a relatively young medium, was unburdened by historical conventions and thus presented itself as a perfect experimental playground. This art form’s flexibility allowed it to be reshaped by techniques that fit Futurist ideals, such as rapid editing, dynamic movement, and visual effects that could alter perceptions of time and space.

For Futurists, cinema held a unique potential as a visual and sensory art form that could mirror the breakneck speed of the modern world. They viewed the moving image as a medium capable of not just telling stories but expressing abstract ideas and emotional intensities. It was a canvas for “wonderful plays” of light, motion, and spectacle. Futurist films were intended to defy traditional narrative structures, avoiding the linear progression of events to instead create an experience of continuous impact and surprise.

Key Figures in Futurist Cinema

The Futurist movement in cinema attracted some of Italy’s most innovative minds. Filippo Marinetti, a poet and the founder of Futurism, saw cinema as a vehicle for the radical changes he envisioned for art and society. Visual artists like Giacomo Balla, a painter known for his depictions of movement and light, and sculptors like Umberto Boccioni, were instrumental in shaping the visual language of Futurist films. Together with others like Armando Ginna and Bruno Corra, they formed a collaborative circle dedicated to experimenting with how cinema could break traditional artistic boundaries.

These artists began experimenting with film techniques even before the official manifesto was published. The films they created pushed the limits of film as an art form, employing visual distortions, layering, and atypical editing styles that highlighted dynamism and abstraction. Futurist filmmakers embraced techniques like overexposure, fast-motion sequences, and non-linear editing, which allowed them to craft a visually chaotic, but conceptually unified experience for the viewer. They saw these techniques as representative of the breakneck speed and instability of modern life.

The Manifesto of Futuristic Cinematography

In 1916, Marinetti and his collaborators published The Manifesto of Futuristic Cinematography, which laid out their vision for a cinema that would break with the past entirely and embrace the principles of Futurism. The manifesto described a new cinematic language that was dynamic, symbolic, and disruptive. Unlike traditional narrative-driven films, the Futurists aimed to create cinema that was “pure” and unencumbered by conventional storytelling. It was to be an art of energy, movement, and symbolic abstraction, not bound to portray realistic events or settings.

The manifesto declared that the Futurist cinema would not simply be a tool for showing images of reality but rather an autonomous medium of expression. This cinema would use speed, disjointed scenes, and surreal visual effects to create a world that captured the essence of modern existence—unpredictable, rapid, and sometimes chaotic.

Key Works and Lost Masterpieces of Futurist Cinema

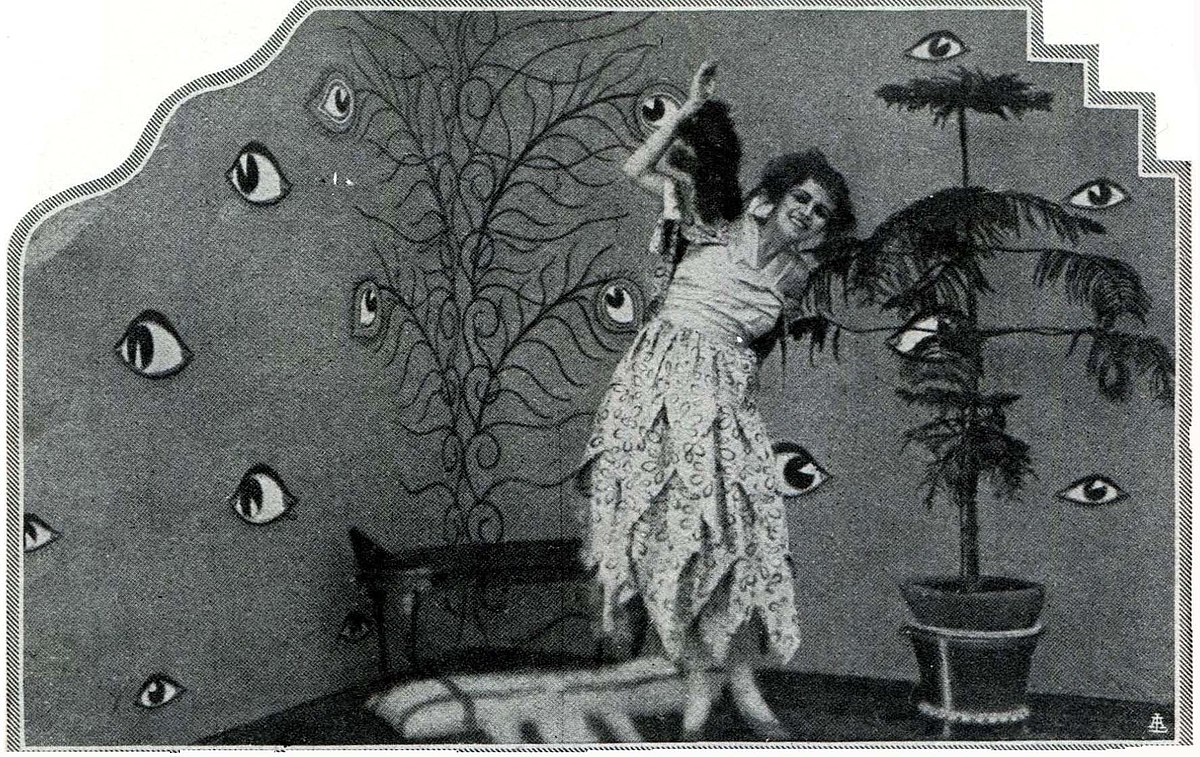

Futurist films were typically low-budget and made with limited resources, resulting in a small output of completed works. Many of these films have unfortunately been lost to time, but some influential titles remain notable for their impact. Among the most significant was Thais (1916) by Anton Giulio Bragaglia. This film is one of the few preserved examples of Futurist cinema, showcasing many of the techniques and themes advocated by the movement.

Thais stands out for its hypnotic and symbolically charged set designs by artist Enrico Prampolini. The film tells the tragic story of Thais, a character whose journey through love and despair was portrayed with heavy use of symbolic imagery, emotional intensity, and dream-like sequences. Prampolini’s expressionistic settings in Thais—characterized by dramatic lighting, exaggerated geometries, and surreal spaces—would later serve as an inspiration for German Expressionist cinema, particularly in films such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).

While few Futurist films were completed or survived, Thais is remembered as a cinematic milestone that bridged Italian Futurism and German Expressionism, and an experiment that paved the way for more abstract and surreal styles in film.

The Legacy of Futurist Cinema and Its Influence on Modern Film

Although the Futurist movement in cinema was brief, its influence continued to resonate. By pushing the boundaries of film’s visual and narrative possibilities, the Futurists inspired later avant-garde movements and experimental filmmakers. Techniques that were once radical experiments—like rapid cuts, fragmented storytelling, and abstract visuals—became part of the cinematic language used in genres ranging from science fiction to music videos.

Moreover, Futurist cinema’s embrace of technology and special effects laid the groundwork for contemporary filmmakers who similarly employ editing, CGI, and other digital techniques to create immersive, non-linear storytelling. Directors such as Federico Fellini, Jean-Luc Godard, and David Lynch have drawn on the Futurists’ abstract techniques to explore narrative disjunctions and psychological themes in their films.

Conclusion

The Italian avant-garde movement of 1911-1919, particularly the Futurist period, represented a pioneering moment in film history. This era not only introduced new aesthetic and technical possibilities but also challenged the traditional purpose of cinema. By embracing speed, fragmentation, and visual abstraction, Futurist filmmakers saw cinema as a powerful tool for capturing the chaos, energy, and transformation of modern life. Though only fragments of this period survive, the legacy of Futurist cinema endures, continuing to inspire filmmakers to experiment with the boundaries of the medium.