The Legacy of Latin in Pre-13th Century Italy

Before the 13th century, Latin was the dominant literary language of Italy, serving as the medium for chronicles, historical poems, heroic legends, hagiographies (lives of saints), religious poetry, and didactic and scientific works. Latin’s prominence was a testament to its role as the language of the Church, education, and intellectual discourse.

However, alongside Latin, early Italian poets also drew heavily from foreign influences. Many wrote in French or Provençal, borrowing extensively in terms of both form and content. Provençal poetry, with its sophisticated structures such as the canzone, introduced themes revolving around the deeds of ancient heroes, Arthurian legends, and the chivalric exploits of Charlemagne and his paladins. These epic tales, initially crafted in a Franco-Venetian vernacular, were later adapted into Tuscan Italian, establishing a foundation for Italy’s chivalric literary tradition.

The Emergence of the Sicilian School

The earliest poetry in Italian emerged from the Sicilian School, a literary movement that flourished under the patronage of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, particularly Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and his son Manfred. Sicily, with its vibrant cultural exchanges fostered by Arab, Norman, and Byzantine influences, became a hub of creativity in 13th-century Europe.

The poetry of the Sicilian School, while written in Italian, lacked distinct native qualities. Instead, it adhered closely to Provençal models, focusing on courtly love themes. Despite its derivative nature, the Sicilian School marked an important step in the evolution of Italian as a literary language. Among its most notable poets were Giacomo Pugliese and Rinaldo d’Aquino, whose works set the stage for later innovations.

The Rise of Regional Literary Centers

Following the fall of the Hohenstaufen dynasty in 1254, Italian poetry found new centers of activity in Arezzo and Bologna. In Arezzo, Guittone d’Arezzo led a movement that adhered to traditional styles but lacked significant artistic innovation. However, Bologna witnessed the emergence of Guido Guinizelli, whose work revolutionized Italian poetry with the creation of the dolce stil nuovo (sweet new style).

Guinizelli’s poetry introduced a Platonic vision of love, wherein the beloved inspired the poet to transcend earthly desires and strive for divine beauty. This spiritualized portrayal of love contrasted sharply with the courtly love traditions of Provençal and Sicilian poetry. Guinizelli’s influence extended to later poets such as Guido Cavalcanti, Cino da Pistoia, and Dante Alighieri, who elevated the dolce stil nuovo into one of Italy’s greatest poetic traditions.

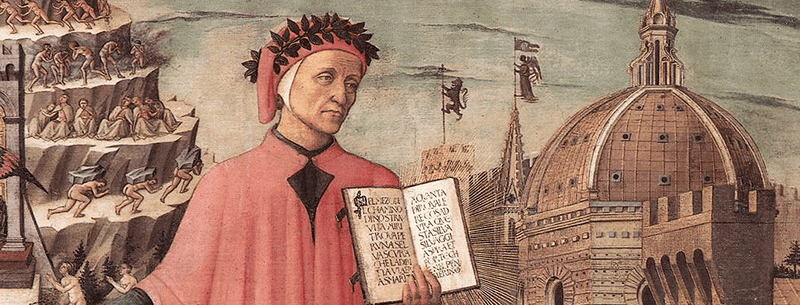

Dante Alighieri and the Flourishing of Italian Vernacular Literature

Dante Alighieri stands as a towering figure in world literature and one of the founders of Italian literary tradition. Deeply influenced by Guido Guinizelli, Dante expanded upon the dolce stil nuovo in his early work, La Vita Nuova (1292; The New Life), which interwove prose and poetry to chronicle his idealized love for Beatrice.

Dante’s advocacy for the Italian vernacular as a literary language was groundbreaking. In his Latin treatise, De Vulgari Eloquentia (Concerning the Common Speech), Dante argued for the legitimacy of Italian as a medium for serious literary expression. This was a radical departure from the dominance of Latin and established the foundation for a vibrant vernacular tradition.

The Divine Comedy: A Masterpiece of Italian Literature

Dante’s La Divina Commedia (The Divine Comedy), composed between 1307 and 1320, remains one of the most celebrated works of world literature. Written in the Tuscan vernacular, the epic poem is a profound synthesis of medieval philosophy, theology, and personal experience. Through its three canticles—Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Paradise)—Dante explores the soul’s journey toward God.

Guided by the Roman poet Virgil and his muse Beatrice, Dante traverses these realms in a work that is both deeply personal and universally resonant. The Divine Comedy is notable not only for its theological depth but also for its vivid depictions of 13th- and 14th-century Italian society, blending allegory with biting social commentary.

Devotional Poetry and the Franciscan Tradition

Concurrent with the rise of secular love poetry, Italy also saw the emergence of a deeply spiritual poetic tradition inspired by Saint Francis of Assisi. Francis’s Canticle of Creatures (Canto dell’ amore), an ode to all of God’s creation, exemplifies this devotional genre. The Franciscan tradition continued with works like Fioretti (Little Flowers), a collection of legends celebrating Franciscan ideals, and the hymns of Jacopone da Todi, whose Stabat Mater remains one of the most enduring works of Christian poetry.

The Impact of Dante and Contemporary Voices

Dante’s influence extended far beyond his lifetime, shaping the works of later Italian authors such as Petrarch and Boccaccio, who enriched Italian literature with their explorations of humanism and individualism. Petrarch’s sonnets and Boccaccio’s Decameron further established Italian as a literary language of unmatched versatility.

In contemporary times, Italian literature continues to evolve, embracing modern themes while remaining rooted in its rich history. Authors like Umberto Eco, with his intellectual thrillers (The Name of the Rose), and Elena Ferrante, whose Neapolitan Novels explore the complexities of identity and friendship, reflect the enduring vibrancy of Italian literary tradition.

Conclusion

From its origins in Latin chronicles and Provençal-inspired poetry to the masterful innovations of Dante and beyond, Italian literature has undergone a remarkable transformation. The elevation of the vernacular not only democratized literary expression but also set the stage for a flourishing national tradition that continues to captivate readers worldwide.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What was the Sicilian School’s main contribution to Italian literature?

The Sicilian School pioneered the use of the Italian vernacular in poetry, establishing a foundation for later literary developments despite its reliance on Provençal models.

2. Who was Guido Guinizelli, and why is he significant?

Guinizelli was the founder of the dolce stil nuovo, a poetic style that introduced a spiritualized portrayal of love, influencing poets like Dante Alighieri.

3. What makes Dante’s La Divina Commedia unique?

Dante’s epic combines allegory, theology, and vivid depictions of 13th- and 14th-century life in a narrative journey through hell, purgatory, and paradise, written in the Italian vernacular.

4. How did Saint Francis of Assisi influence Italian poetry?

Saint Francis inspired a tradition of devotional poetry that celebrated God’s creation and spirituality, exemplified by works like the Canticle of Creatures.

5. Why did Dante write in the Italian vernacular?

Dante sought to make literature accessible to a broader audience, advocating for the vernacular as a legitimate medium for intellectual and artistic expression.

6. How has modern Italian literature evolved from its medieval roots?

Contemporary authors like Umberto Eco and Elena Ferrante draw from Italy’s literary heritage while addressing modern themes, showcasing the enduring relevance of Italian literature.